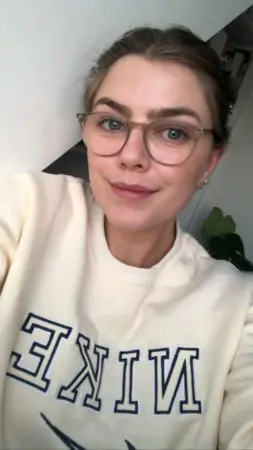

Eleanor’s story: “Looking back at it now, I don’t know how I did it”

“They found it very distressing to drop me off in a seemingly good state and pick me up and help me hobble back home in a horrible drowsy and sick state. I think for them, not seeing the progression of the treatment taking place made it hard to process and just shocking every single time I had chemo.”

When Eleanor was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma at the height of the pandemic, she was alone for much of her treatment. During six months of chemotherapy, she struggled both mentally and physically after experiencing numerous side effects.

“It was a complete shock to my body,” she said. “Straight away I had every single symptom and side effect that they knew of. I was neutropenic for my first three cycles so really fragile.

“I felt so, so sick, I could hardly move, I had really bad jaw pain and mouth ulcers, I started getting weird skin reactions and I lost my appetite. My hair started to fall out after my second cycle, I also got a bit of neuropathy – I spent nights twitching, my muscles were in spasm. I lost all my hair and was really quite ill a lot of the time. I didn’t have much recovery time, especially at the start, I would only have a couple of days where I felt okay before I had to go in for the next one. That was the hardest bit really.

“My veins really didn’t like it so I had to get a PICC line. I was put on really heavy sedatives for the sickness and lorazepam for my anxiety around it. There were a lot of side effects and I don’t think any of us realised how hard it would be, my doctor just says I was just particularly unlucky with how I reacted to it.”

When Eleanor found a lump on her neck in May 2020, her mum, a former nurse, encouraged her to call her doctor. Eleanor, who was 21 at the time, saw her own GP before having blood tests, an ultrasound and biopsy which led to a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma a month later.

Eleanor was alone when she received the news over the phone.

She said: “I didn’t have a face-to-face consultation when I found out it was lymphoma. That was the worst thing about it, especially because my blood test came back fine so I was given a false sense of security.

“I had a consultation booked, over the phone, I was waiting around on that day and nobody called – I was waiting for big news either way, even though I felt like I was expecting good news because I felt like it was nothing. It wasn’t until two days after that I got a phone call from the ear, nose, throat department who gave me my biopsy – it wasn’t the oncology department – they called me and told me but he didn’t have much information because it was the wrong department, he basically said ‘it’s come back as Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, we don’t have a specific type.’

“He said that it needed to be tested a bit more and he said ‘do you have any questions?’ I said I do and he replied ‘well I’m not sure I’m going to be able to answer them because that’s not my speciality’. Obviously I was distraught and I wasn’t thinking clearly and I sort of said ‘okay, that’s fine’, held it together and ran down and told my parents.”

Eleanor said that the rules around having treatment alone isolated her from her family.

“I think they felt very out of the loop especially with consultations. By the end of it I’d gotten so used to going in on my own, that I didn’t see any point in them coming in. It became normal for me to handle it on my own and I think they struggled with not being able to help more. My mum would end up emailing my nurse and asking him for the information so she was kept in the loop because it was difficult for me to re-live every consultation whenever I got home.

“They found it very distressing to drop me off in a seemingly good state and pick me up and help me hobble back home in a horrible drowsy and sick state. I think for them, not seeing the progression of the treatment taking place made it hard to process and just shocking every single time I had chemo. Altogether it was quite a draining process for everyone involved.

“A lot of families would have sat there during the chemo or during horrible hospital trips and mine hadn’t so there was a big difference in our experiences of it all which makes things difficult when you’re trying to support one another through it.”

Eleanor opted to focus her energies on getting better.

“I think it was so fast-paced and I was in such a bubble that nothing else really was on my radar apart from just getting through every day as it came,” she said. “Especially with the pandemic, as I was in a vulnerable position any changes to the rules or anything like that didn’t affect me because I had to stay inside and away from people so with that in mind, I didn’t watch any of the news, I didn’t keep up to date with it.

“That was hard when things relaxed, I started feeling anxious that one I was missing out and two that this was going to get me. People became a lot more relaxed and thought that they were invincible, yet I still felt so fragile. Bournemouth beach was so packed that even my daily walks were stripped away from me because it was just too dangerous, which didn’t help because you get cabin fever.”

Despite undergoing intensive chemotherapy, Eleanor was determined to finish the final year of her French and Spanish degree when diagnosed.

“I decided to carry on. I knew that it was going to be very hard, I knew that I had chemo every other week and I knew that I had hospital appointments in between. I hated the idea of giving up or not graduating with my friends. I think I was running on pure adrenaline. I would have a chemo session on the Monday, I would feel ill until about the Saturday/Sunday and then I would power through the next week, do all my work and try to get ahead knowing that by Monday, I would be bed ridden again and I was just on that constant loop.

“Looking back at it now, I don’t know how I did it but you find the energy somewhere. In my head there was no other option, in my head education and my health had equal priority so they took equal parts in my life. On top of my studies, I was also the president of a dance society at Cardiff, I did that all remotely – I micro-managed the girls so they all knew what they were doing. I also co-founded a company during that time as well.

“Some people thought I was mad for carrying on with it all but I would have been doing those things normally and I didn’t want to feel like I would finish this cancer journey and have missed out on those things and not have had those experiences just because I had cancer. It was this mindset that I didn’t want cancer to affect my future as well as my present.”

Eleanor, who is now in remission, also received the news that she was cancer-free over the phone.

“I was writing an essay in my room and I got a call from my nurse and it was two minutes long, he told me I didn’t have cancer anymore and that was that. I was like ‘what am I supposed to do with this now?’

“That is the biggest downfall of Covid, I wasn’t able to properly celebrate and I just felt very, very deflated. After the call, I went downstairs to my family and was like ‘I don’t have cancer’ and we went back to doing whatever we were doing before. That was so disappointing because I had been looking forward to that moment the whole time and I had built it up in my head. Normally I would have had my friends round and had a drink and really made a day of it and I couldn’t do that which meant I didn’t have much closure.

“The problem is a lot of people – friends and even family – they just forget about it, they don’t mean to, but life moves on and it will never be as big of a part of their lives as it was for you. There’s a part of me that doesn’t feel like celebrating, I feel like there’s a long journey left to get through. The only thing that had changed was that I wasn’t having chemo anymore, it didn’t feel like a cause for celebration really for me and I think that was just reiterated by being locked down.”

Eleanor was supported by a Young Lives vs Cancer social worker and was introduced to Facebook groups which she found useful.

“Mainly it was financial support, I got the initial grant and I had a nice few chats with Amanda who was my social worker, by phone. She was actually the one that made me aware of my anticipatory nausea and gave me some resources saying what it was and things that could help it. She gave me information on how to apply for more help from university and disability services.

“With the Facebook group – I met a couple of people on that. It really helped in finding people to moan to, without explaining what I was moaning about. It gives you a sense that you’re not alone or you’re not crazy for thinking a certain way. There’s no stupid question to ask. It’s a really nice environment to be in and there’s where I thrive where I know that whatever I say somebody else is probably going to relate to it.”

Posted on Friday 14 January 2022